Setting up Nginx with LetsEncrypt certificates

If you're setting up a web application (or even a testing/staging server for one), sooner or later you're going to have to bite the bullet and do it properly. Assuming that you're deploying a non-PHP type application (Ruby, Node.js, Smalltalk, Go, and the like), you will need to do the following:

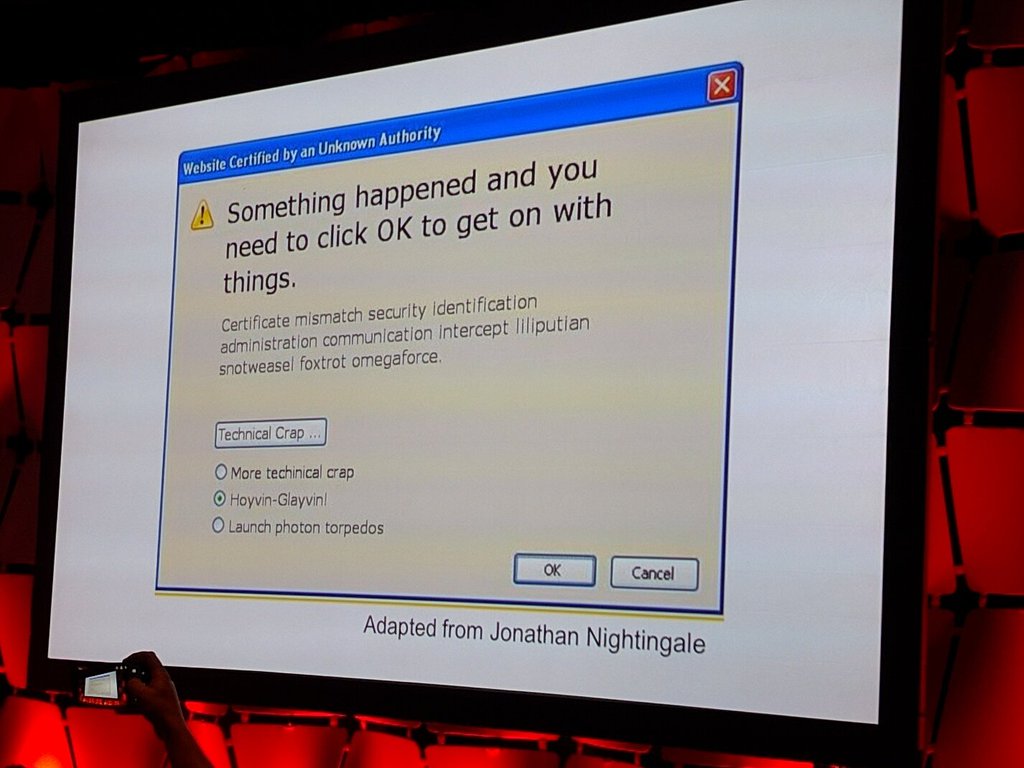

- Get yourself a proper SSL certificate (self-generated certs won't cut it). Hopefully I don't need to convince you that you shouldn't be running any sort of web app involving users over a plain-text HTTP connection.

- Put your app behind a real front end/webserver/proxy, and not just run your app as root via

sudo node app.json port 80/443 like a hobo. This means: Nginx, Apache, or HAProxy (or, in some obscure cases, some combination of the 3).

Incidentally, you'd be surprised at how hard some developers argue and drag their feet about that second point. Sure, you can run your app as root on port 443 for a few minutes, just to test everything is working. But don't even think about leaving it deployed like that, not even on a testing server. No, not even if the app is trivial and there isn't sensitive data at stake. There is a reason that front-ending apps with Apache/Nginx/whathaveyou is an industry best practice.

Also, it's not that difficult to do, so you have no excuse. Let's walk through the procedure.

Step 0: Pre-Requisites

This post assumes that you've spun up a server and set up its domain name. Specifically:

- You have a domain name (here, we'll use

example.com). - You have access to a server (an inexpensive VPS instance from Digital Ocean, Scaleway or Amazon AWS works great). I'll be using Ubuntu here, but the instructions are almost identical for CentOS and others.

- You've pointed your domain registrar's DNS records to your VPS host's NS servers (so, if you're using DO, your Custom DNS Server entries at the registrar will point to

NS1.DIGITALOCEAN.COM,NS2. ...and so on) - You've set up the proper DNS records (

Arecord, and aCNAMErecord for any subdomain) on your VPS host's Networking/DNS tab. In this example, we'll be setting up Nginx to point totest.example.com, so we at least need a*CNAMErecord added to support that subdomain.

Step 1: Obtain an SSL Certificate with LetsEncrypt

SSL Certificates from recognized Certificate Authorities used to be quite expensive. For example, that's how Mark Shuttleworth, of Ubuntu/space tourism fame, partly got his fortune -- by selling SSL certificates back in the day. Over the years, they have come down in price, but even now, if you want to get a Wildcard certificate (so that it covers arbitrary subdomains), you're looking at anywhere from $85 USD to $500+ per year.

Fortunately, there's also LetsEncrypt.org. LetsEncrypt is a remarkable service -- a legit Certificate Authority (CA) that gives you SSL certificates for free, and gives you a command-line client that lets you do this programmatically.

While LetsEncrypt doesn't offer wildcard certs, they do let you include multiple subdomains in a single certificate, and offer very reasonable rate limits. Also, chances are good that you don't need a wildcard certificate anyway, since you're probably not running a user-facing hosting service.

Docs: see the LetsEncrypt.org Getting Started Guide and the Full Docs for more information.

Installing the LetsEncrypt Client

Pre-requisites: Make sure you have openssl installed. (Also, if you're going to install from the certbot repo, make sure you've also installed git.)

Installation via apt-get or similar: The main page has OS-specific installation instructions (you just have to select your OS from the pulldown, as well as what webserver (Apache, Nginx, etc) you'll be using with it. For example, here's their Ubuntu 16 + Nginx installation docs. Assuming you're on Ubuntu 16.04 (xenial):

sudo apt-get install letsencrypt

Installation from git repo + script: Alternatively, you can just install the certbot-auto wrapper script directly from its repo (which is what I did). See the Installing Client Software section of the getting started guide.

Understanding LetsEncrypt Plugins

It took me some confusion and experimentation to understand the various letsencrypt plugins. Did I need an "authenticator" or an "installer"? Since I wanted to use the certificate with Nginx, did I need the Nginx plugin? (Answer: the Nginx plugin is either not available or completely undocumented, which is the same thing. So no, you don't need it.)

If not the Nginx plugin, did I need to go the standalone or the webroot route? Or maybe manual?

Eventually, I sorted it out. Since LetsEncrypt.org is a Certificate Authority, their main goal is to verify that you control the domain for which they are issuing a certificate. To do that, the LetsEncrypt client needs to do a back-and-forth call and response dance with their servers. Which means that you have only a few options.

Simplest route: --standalone

If you can afford to stop your webserver (and let the client take over the HTTPS port for a second), you can just use the --standalone plugin to verify your domain (to generate your certificate). This is perfect for when you're first setting up your server, or cases when momentary downtime is ok (if it's not a user-facing production service).

In the following example, I'm using the letsencrypt-auto script from the repo, but if you installed the client from an OS package (like via apt-get), the command line parameters should be the same:

Here is how you would generate a certificate (that's the certonly command) using the --standalone plugin (which requires you to stop Nginx or whatever else service is using port 80 and 443) for two different subdomains (example.com and test.example.com):

./letsencrypt-auto certonly --standalone -v \

--email your@email.com -d example.com \

-d test.example.com

Several things to notice here:

- This generates the certificates in

/etc/letsencrypt/live/example.com/(thelivedirectory actually contains symlinks to the latest generated certificates) - The link to the latest certs becomes relevant later, since you'll need to renew your certs every 90 days.

- This command actually generates a single certificate for both subdomains (or however many you listed using the

-dflags). This means that if you have a finite amount of subdomains (as opposed to an arbitrary number of user-created subdomains), you can easily list them as one entry (plus aliases) in the Nginx setup, and use just one certificate path (as you'll see in the example below). - The

--emailis optional but helpful (LetsEncrypt will send you reminder emails that your certs are about to expire).

If you have an existing Nginx that you cannot stop/start: use --webroot. The --webroot plugin allows the LetsEncrypt client to verify your domain without stopping your existing server and taking over ports 80 and 443. It does this by placing some files in a directory you specify (which, again, lets their servers know that you actually control your domain).

This route is slightly trickier, since you have to create the --webroot-path (or just -w) directory, make sure Nginx has read/write access to it, make sure that there's an entry for it in sites-available and so on. But if you have an existing Nginx installation, and cannot afford a moment of downtime, you don't have many other choices.

The general idea is the same: use the certonly command with the --webroot plugin, list the domain and subdomains you want a certificate for with the -d flag, and specify a webroot path directory (-w) which the client can use to create the /.well-known/acme-challenge directory it needs for verification.

For example (assuming you have the /var/www/example.com directory created and set up in the Nginx config):

./letsencrypt-auto certonly --webroot -w /var/www/example.com -d example.com -d test.example.com --email your@email.com

Step 2: Set up Nginx

Once you have your certificates generated, it's time to set up Nginx to use them (and to serve as a front end / reverse proxy for your web application).

(See also: https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/how-to-secure-nginx-with-let-s-encrypt-on-ubuntu-14-04 for a more thorough walkthrough, and http://maxogden.com/https-wildcard-nginx-setup.html)

(Optionally) Generate a strong Diffie-Hellman group:

openssl dhparam -out /etc/ssl/certs/dhparam.pem 2048

Edit the Nginx config file for your site (for example, edit /etc/nginx/sites-available/example.com):

server {

root /usr/share/nginx/html;

index index.html index.htm;

listen 443 ssl;

server_name example.com test.example.com;

ssl_certificate /etc/letsencrypt/live/example.com/fullchain.pem;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/letsencrypt/live/example.com/privkey.pem;

ssl_protocols TLSv1 TLSv1.1 TLSv1.2;

ssl_prefer_server_ciphers on;

ssl_dhparam /etc/ssl/certs/dhparam.pem;

ssl_ciphers 'ECDHE-RSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256:ECDHE-RSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384:DHE-RSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256\

:DHE-DSS-AES128-GCM-SHA256:kEDH+AESGCM:ECDHE-RSA-AES128-SHA256:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-SHA256:ECDHE-RSA-AES128-SHA:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-SHA:ECDHE-RSA-AES256-SHA384:ECDHE\

-ECDSA-AES256-SHA384:ECDHE-RSA-AES256-SHA:ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-SHA:DHE-RSA-AES128-SHA256:DHE-RSA-AES128-SHA:DHE-DSS-AES128-SHA256:DHE-RSA-AES256-SHA256:DHE-DSS-AES2\

56-SHA:DHE-RSA-AES256-SHA:AES128-GCM-SHA256:AES256-GCM-SHA384:AES128-SHA256:AES256-SHA256:AES128-SHA:AES256-SHA:AES:CAMELLIA:DES-CBC3-SHA:!aNULL:!eNULL:!EXPORT:!D\

ES:!RC4:!MD5:!PSK:!aECDH:!EDH-DSS-DES-CBC3-SHA:!EDH-RSA-DES-CBC3-SHA:!KRB5-DES-CBC3-SHA';

ssl_session_timeout 1d;

ssl_session_cache shared:SSL:50m;

ssl_stapling on;

ssl_stapling_verify on;

add_header Strict-Transport-Security max-age=15768000;

# Reverse proxy to Connect

location / {

proxy_buffering off;

proxy_set_header Host $http_host;

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-Proto $scheme;

# untested, but taken from https://gist.github.com/nikmartin/5902176#file-nginx-ssl-conf-L25

# and seems useful

proxy_set_header X-NginX-Proxy true;

proxy_read_timeout 5m;

proxy_connect_timeout 5m;

proxy_pass http://localhost:3000;

proxy_redirect off;

# Static files

location ~* .+\.(ico|jpe?g|gif|css|js|flv|png|swf)$ {

# http context

proxy_cache backcache;

proxy_buffering on;

proxy_cache_min_uses 1;

proxy_ignore_headers Cache-Control;

proxy_cache_use_stale updating;

proxy_cache_key "$scheme$request_method$host$request_uri$is_args$args";

proxy_cache_valid 200 302 60m;

proxy_cache_valid 404 1m;

proxy_pass http://localhost:3000;

}

}

}

Note the proxy_pass line -- it assumes that your web app (Node.js or whatever) will be listening on http://localhost:3000.

Extra Credit

- Start up Nginx, fire up your web app, and use the SSL Server Test page to make sure the SSL/cert part of your app is set up properly.

- Set up a firewall (UFW for Ubuntu makes for an extremely easy to use firewall package), and close off the ports you don't need.

- Make sure your app is running as a service, using either your OS's startup daemons (such as

upstartor better yetsupervisordfor Ubuntu), or a language-specific service runner (such as the excellentpm2for Node.js). - Set up logging

- Set up monitoring